Hip Arthroscopy

Introduction

This information sheet is aimed to provide a general guide to the common indications for hip arthroscopy, what to expect if undergoing the surgery, the significant risks, and a general guide to the expected recovery pathway. This document is not by any means fully comprehensive, and any particular questions should be addressed with your surgeon. Many different hip procedures can be performed arthroscopically, and from country to country, and surgeon to surgeon, there will be significant variations.

Indications for Hip Arthroscopy

Since the early 20th century, when hip arthroscopy was regarded as being almost impossible to undertake, the procedure has developed in leaps and bounds. Presently there are many reasons why a surgeon might recommend hip arthroscopy to a patient. Some of these reasons are as follows:

- To explain unexplained hip pain (diagnostic hip arthroscopy)

- Removal of loose or foreign bodies

- Repair of damaged articular cartilage (gristle)

- Removal or repair of a torn acetabular labrum (see below)

- Correction of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI – see below)

- Management of damaged hip ligaments, e.g. ligamentum teres

- Management of hip joint infection

- Inflammation of the hip lining (synovitis)

- Investigation of a painful joint replacement or hip resurfacing

- Management of internal and external snapping of the hip including psoas and iliotibial band impingement

- Trochanteric Bursitis

- Hip Instability

- Repair of tears of the gluteus medius and minimus

Perhaps the two most common current indications for hip arthroscopy include the presence of symptomatic FAI or an acetabular labral tear, or both. These will be considered in more detail here:

Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI)

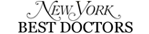

FAI is a condition affecting the hip joint (Figure 1) and is characterised by abnormal contact between the femoral head (hip ball ) and the rim of the acetabulum (hip socket) leading to damage to the articular cartilage (lining or gristle) in the acetabulum, or to the labrum of the hip, or both. The labrum is a ring of cartilage that surrounds the acetabulum and looks very like the meniscus of a knee joint, although its function is different. Damage to the labrum and/or articular cartilage will likely cause pain. An abnormality in the shape of the femoral head or acetabulum, or both, may cause FAI. Activities that involve recurrent hip motion can increase the frequency of this abnormal contact, e.g. kicking sports. FAI generally presents in three forms: cam impingement, pincer impingement and mixed impingement (involving both cam and pincer type). FAI can affect all age groups from the early teens to throughout adult life and is being increasingly recognised as one of the predisposing factors for osteoarthritis of the hip. Although scientific evidence is still slightly sketchy, it is felt by many that without early intervention surgery, there is a high likelihood of developing osteoarthritis (‘wear and tear’), with the subsequent requirement for either a hip replacement or other major hip operations. Hip arthroscopy can be used to reshape the femoral head and socket to prevent impingement, and aims to protect the hip from developing osteoarthritis, as well relieving current symptoms.

Acetabular Labral Tears

The labrum, which surrounds the acetabulum, can be partially damaged or torn. This is usually associated with FAI, but not always so. With hip arthroscopy, the labrum can be either debrided (remove the damaged tissue only) or repaired. Occasionally a labrum can also be grafted. MRI and/or CT scans, although often performed before hip arthroscopic surgery is undertaken, do not always reveal every labral tear.

Length of stay in Hospital

- Hip arthroscopy is ambulatory surgery meaning you can go home the same day of surgery.

Anesthesia

- The surgery is performed under general anaesthetic most commonly but not always. If a general anaesthetic is given then there may be an additional regional local anaesthetic block.

How we perform hip arthroscopy

- The bones of the hip joint (the ball and socket) are separated by approximately 1cm by applying traction to the foot while wearing a special boot. By distracting the hip, this provides enough room for a small telescope (‘arthroscope’) to be introduced into the joint. Initially, air and/or fluid are injected into the hip, under x-ray guidance. Once correct placement of the instrument has been confirmed, two, three, or sometimes four small incisions are made on the side of the hip. Each of these incisions generally measures approximately 5-10 mm in length.

- Through these small holes, the telescope and instruments are passed into the joint. The surgeon will then be able to visualize the hip joint, identify the problem(s), and proceed appropriately. Very occasionally it is not possible to insert an arthroscope into the hip joint. The operation duration will vary depending on the problem in the hip joint but can last from 30 minutes to 120 minutes, or even more. During the surgery, further x-rays may be taken, for example, to confirm adequate removal of bone.

- At the end of the procedure medications may be injected into the hip to minimise pain after the surgery. The small holes are often closed with one to two stitches each or tapes, although some surgeons choose to let the wounds heal naturally, without closure. Finally, a further dressing is placed over the holes.

After hip arthroscopy

- Usually, you will feel some discomfort in your hip. In addition, the discomfort can be experienced in the lower back, buttock, knee and ankle. The discomfort can normally be reduced with the appropriate pain relief. In the majority, there will be some swelling in the groin, buttock and thigh. This is caused by the fluid used during the surgery. The swelling reduces over the following few days.

- You are likely to be seen by a physiotherapist following your surgery. They will make sure you are safe to mobilize with or without the aid of crutches. This will depend on the instructions received from your surgeon. In most circumstances you may be asked to limit the amount of weight you put through your operated leg, while in others you may be allowed to fully weight-bear immediately after surgery. Consequently, you may require crutches for a few days, or weeks, depending on what specific surgery has been undertaken. Your surgeon and physiotherapist will decide when it is appropriate for you to stop using the crutches.

- Observe the wound for any signs of infection (increasing pain, redness or swelling). The skin incisions can sometimes leak fluid or blood slightly for a few days; this is normal.

- At a variable point after surgery you will be reviewed by your surgical team. At this appointment, your wound may be inspected and, in some cases, the sutures removed if that has not already been performed. A further explanation of the surgery undertaken can then be provided and there will also be an opportunity for specific queries to be answered. Any subsequent appointments will be arranged and will be guided by the surgery performed.

- Your surgeon and physiotherapist will develop an appropriate rehabilitation programme for you following the surgery. Your physiotherapist will guide your return to sporting activities (running etc.) depending on your progress. This is extremely variable between individuals, depending on the surgical findings and the length of symptoms prior to surgery.

- In the majority, by 8 weeks after surgery you should be walking relatively pain-free. Remember, however, that it may take 6 months or more to return to an elite level of competition/fitness. Any unexpected increase in pain can be treated with ice packs and anti-inflammatory medication. The broad strategy for rehabilitation is to regain early range of movement and stability, followed by strength and endurance. Return to work will depend on pain levels and the nature of your job.

- There are some activities to avoid or take care with up to 8 weeks following surgery. These include the following:

- Prolonged standing, especially on hard surfaces

- Prolonged walking i.e.; around shopping centres

- Heavy lifting

- Squatting / crouching

- Sleeping on your side. Try to sleep on your back. If you must sleep on your side, sleep on the unoperated side, with a pillow under your operated leg – to hold that leg level with the body

- Clutch use in manual cars (for left hips) – may flare up symptoms in the first couple of weeks and is best avoided. Exchange cars if possible

- Sitting with the hips at 90 degrees – a more open seat angle is recommended i.e.; 120 degrees. Car seats should be tilted backwards slightly in order to open the hips out

Please note that these are only suggestions for minimizing discomfort/pain. Your surgeon and/or rehabilitation team may have further ideas and you should listen to them carefully.

Potential risks and complications of hip arthroscopy

- All surgery carries risks, although every effort is made to minimise them. The complications can be temporary or permanent. Reassuringly, permanent complications following hip arthroscopy are rare and the majority are temporary. There are, however, risks which include the standard risks of undergoing general anaesthesia and specific risks associated with hip arthroscopy.

- Complications have been reported to occur in up to 5% of patients and are most often related to temporary numbness/altered feeling in the groin and genitalia. This is due to a combination of distraction of the hip joint and pressure on the nerves in the groin at the time of surgery. This is uncommon and although there is a theoretical risk that this numbness could be permanent, in the majority the numbness recovers fully, usually within a few days. Other complications might include, but are not limited to: pressure sores and blistering, infection, fracture, increased pain, impotence, bleeding, nerve palsies, abandoned procedure, deep-vein thrombosis, instrument breakage, avascular necrosis of femoral head, extravasation of irrigation fluid, delayed wound healing, exacerbation of symptoms. However, many of these complications are extremely rare. For example, the exact rate of infection following hip arthroscopy is unknown, but would certainly appear to be substantially less than 1 in 1000.

9673 Endoscopic Sciatic Nerve Decompression for Deep Gluteal Syndrome

Ischiofemoral Impingement

Gluteus Maximus Tendon Transfer

Endoscopic Partial Proximal Hamstring Repair

Hip Labral Repair and FAI Surgery: complete surgery from setup to repair

Hip Labral Reconstruction Using Fascia Lata Allograft

Arthroscopic Treatment of Avascular Necrosis (AVN) of the Femoral Head

Enrique Ergas, MD, FACS Thomas Youm, MD, FACS Hip Arthroscopy Hip Arthroscopy

Hybrid Knotless and Knot-tying Labral Repair

Two Anchor Knotless Labral Repair

Hip Dysplasia & Capsule Repair

Hip Capsule Repair

FAI Prophylactic Surgery

Arthroscopic Assisted Core Decompression of the Hip

Endoscopic Gluteus Medius Repair by Dr Thomas Youm

You will need the Adobe Reader to view and print these documents

Guidance prepared on behalf of the International Society for Hip Arthroscopy (www.isha.net)

Authors: Singh PJ*, O’Donnell JM**, Pritchard MG**

*Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, Oxford, UK

**Mercy Private Hospital, East Melbourne, and Bellbird Private Hospital, East Blackburn, Victoria, 3121, Australia